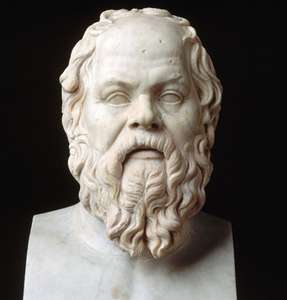

The earliest proponent of the division of labor I’m familiar with is Socrates. In Plato’s Republic, for example, he argues for why we each must choose a profession and work at it – that all work requires a kind of devotion – if we want to become proficient enough to produce useful goods and services. For him, being productive depends on possessing specific skills and knowledge, the acquisition of which depends on time, practice, and inclination.

This need for specialization is one reason he bemoaned the workings of Athenian Democracy: just as you wouldn’t choose your physician or ship’s captain by lot and therefore at random, you shouldn’t choose your legislators and governors that way either.

His basic observation raises some interesting questions. Have you ever tried to catalog what you know that makes you capable of doing your work well – whatever it is? Likely it would be an extensive list of items large and small. Some you learned long ago, some recently; some from others, some you taught yourself. Possibly there are things you plan to learn still, in order to improve.

Whatever your specifics, being aware of the knowledge underlying what you do and why can shed light on just how involved the act of production is, and how much credit you – and we – deserve for doing it.

Be First to Comment